Michael Mann is a difficult filmmaker. His style is ugly on purpose, especially since he started playing with digital cameras while making Ali in 2000, and he isn’t particularly interested in engaging the audience. On the surface, he makes action movies, but his movies, even the less-good ones—I don’t think Michael Mann ever really makes a bad movie, just one that’s less good than the others—are never just an action movie. Blackhat, Mann’s first movie since 2009’s Public Enemies, looks like any run of the mill action-thriller, and by rights ought to have been terrible (certainly most people thought it was anyway).

But Blackhat is not terrible. Oh sure, it’s unpleasant. It’s ugly as sin to look at times, and the cybercrime plot is inherently uninteresting. Hackers and the virtual world are just not visually engaging, and despite an effort at rendering the micro-processes of computers with some sort of style, Mann does not solve that problem. Blackhat has an unexpected twist up its sleeve, though, one that makes it worth salvaging as an artifact of Mann’s career—it’s a 21st century update of The Last of the Mohicans, one of Mann’s most popular and accessible films. The twist is that unlike Mohicans, which is very interested in engaging its audience, Blackhat doesn’t care at all if people actually like it. Blackhat, more than any Mann movie to date, represents a filmmaker alienated from his audience.

To be clear, even if history revises Blackhat upward—as it did with Thief and Manhunter—it will never be anything but a minor work in Mann’s oeuvre. It has problems, chief among them the boring visual nature of cybercrime, that will keep it from the ranks of the more-good Michael Mann movies. But after reading a slew of terrible reviews and then seeing the movie, I had to ask myself—when did everyone decide to stop liking Michael Mann? Blackhat has problems, yes, but it’s also quintessentially a Mann movie. Mann’s style is on full display—down and dirty digital lensing, jets, cars, gun fights, lone wolf heroes, beautiful smart women, doomed lovers, it’s all there. And Mann’s philosophical curiosity remains intact as well—divisions and boundaries melting away as technology advances, the constraints men put on women, and unique to Blackhat, the role of geopolitics within the world of cybercrime, which often knows no country.

The Last of the Mohicans and Blackhat are, at heart, the same story set in disparate eras. They’re both “doomed lovers on the run” narratives, with the loner hero having an edge because he is the Most Superior with a specific piece of technology, and his love interest chafes against the boundaries placed on her by men. It’s not a big leap from Hawkeye to Blackhat’s Hathaway—their echo-chamber names cannot be coincidental—which is when the improbable casting of towering blonde Adonis-monster Chris Hemsworth as Hathaway started to make sense. In Mohicans, Daniel Day-Lewis brought an overwhelming physicality to Hawkeye, and Hemsworth does the same for Hathaway. Hemsworth as an elite hacker isn’t that odd when Hathaway is read as a modern-day Hawkeye.

Like Hawkeye, Hathaway begins the film in isolation. As the white adopted son of a Mohican man, Hawkeye’s isolation is metaphorical; Hathaway’s, however, is literal—he’s in prison. Their conflicts are similar, too. Hawkeye is forced into an uncomfortable truce with people who loathe and fear him, and so is Hathaway, furloughed from prison to help the FBI. But with Hawkeye there is a sense of hope to his conflict, a feeling that if he can survive, everything just might work out. Sure, his post-narrative future with the resourceful Cora (Madeleine Stowe) will be a hard, fraught life on a brutal frontier, but men like Hawkeye—self-determining alphas who live beyond the bounds of society—excelled in that place and time. Twenty-three years later, that hope is gone from Hathaway’s similarly “happy” ending. The final image of Hawkeye and Cora looking out over their frontier at the end of Mohicans is inspiring; the image of Hathaway and his similarly resourceful partner, Lien (Tang Wei, Lust, Caution), is much less comforting as they’re observed making their getaway on surveillance cameras. They’re the watched, not the watchers.

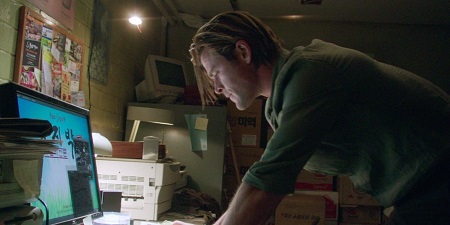

Perhaps the closest analog for the filmmaker in a Mann movie, Hathaway is alienated and alienating. He’s hemmed in by technology as much as he’s freed by it, as is Mann. He was an early auteur aboard the digital train, but it seems he’s the only one exploring what digital can do that celluloid film can’t. From the onset of the technology the goal has been to make digital cinematography look “as good” as film. That’s not bad, in and of itself; some filmmakers have created very beautiful and rich results with digital, such as Roger Deakins’s work on Skyfall or Harris Savides lensing Zodiac. But Mann isn’t interested in polish. Grit and grain are an intrinsic part of his visual language, a physical representation of his unique, unglamorous examination of crime and criminals. Miami Vice has the same grainy, ugly video look to it that sucks all the 1980’s neon glitz out of a drug war cautionary tale. Blackhat is ugly, so too is the world of cyberterrorism.

Blackhat is not for everyone. It’s not slick, it’s not polished, it’s not interested in being your friend. But it earns its place in Mann’s continuing study of crime and criminals. Once, it was bank robbers and thieves, now it’s hackers and terrorists. That cybercrime is not visually interesting to watch is a problem, one Mann doesn’t overcome. Because of that, Blackhat feels less like an achievement and more like a stepping stone as Mann tries to get a handle on modern crime sagas that involve more computers than guns. Hopefully, we’ll get to see the next movie in that chain, but I’m not sure what the future holds for Mann. More than any other contemporary American filmmaker, it seems we’ve lost patience with his style and interests. It feels like we’re leaving Michael Mann behind, and that is not a good thing.